A Split Panel of the Federal Circuit Reverses PTAB Finding of Unpatentability Without Remand in DSS v. Apple

In DSS Technology Management v. Apple Inc., a split panel of the Federal Circuit reversed a finding of patentability by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB or the Board), but did so without remanding the case back to the Board for further findings.

In DSS Technology Management v. Apple Inc., a split panel of the Federal Circuit reversed a finding of patentability by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB or the Board), but did so without remanding the case back to the Board for further findings.

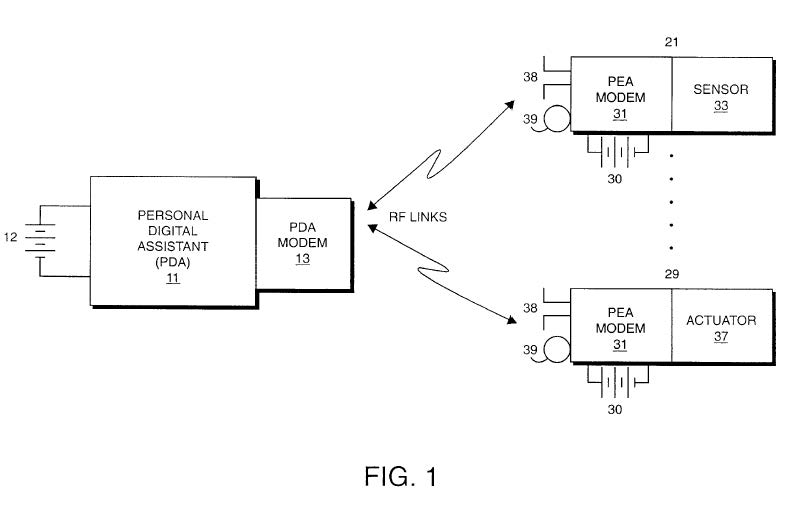

The ’290 patent teaches that the transmitters within the host or server microcomputer and the peripheral units in the data network operate in a “low duty cycle pulsed mode of operation.” Claim 1 is representative of claims 1-4 and 9-10 in appeal:

The ’290 patent teaches that the transmitters within the host or server microcomputer and the peripheral units in the data network operate in a “low duty cycle pulsed mode of operation.” Claim 1 is representative of claims 1-4 and 9-10 in appeal:

1. A data network system for effecting coordinated operation of a plurality of electronic devices, said system comprising: a server microcomputer unit; a plurality of peripheral units which are battery powered and portable, which provide either input information from the user or output information to the user, and which are adapted to operate within short range of said server unit; said server microcomputer incorporating an RF [radio frequency] transmitter for sending commands and synchronizing information to said peripheral units; said peripheral units each including an RF receiver for detecting said commands and synchronizing information and including also an RF transmitter for sending input information from the user to said server microcomputer; said server microcomputer including a receiver for receiving input information transmitted from said peripheral units; said server and peripheral transmitters being energized in low duty cycle RF bursts at intervals determined by a code sequence which is timed in relation to said synchronizing information.

The DSS panel determined that the only disputed limitation was the last limitation, which requires that the transmitters on both the server microcomputer and the peripheral units must be energized in “low duty cycle RF bursts.” The IPRs To institute the resulting IPRs, the Board relied on two pieces of prior art in the IPR: U.S. Patent No. 5,241,542 to Natarajan et al. (“Natarajan”), and U.S. Patent No. 4,887,266 to Neve et al. (“Neve”). In its final written decisions, the Board found that the combination of these references rendered obvious all of the challenged claims of the ’290 patent. Natarajan was relied upon for its power conservative wireless communications with portable units. It provided time slots when the mobile units could turn communications off because it was outside its appointed time slot for receiving and transmitting data. In the IPRs, Apple argued that because the mobile units of Natarjan were operating in “low duty cycle RF bursts” it would have been obvious for the base station to operate in an analogous manner. Apple argued that the base and mobile stations have the same physical structure and would operate similarly using the known technique applied to the mobile units of Natarajan. DSS countered that Natarjan says nothing about applying the low power approach to the base station transmitter. DSS also pointed out hat the base station used a different communication scheme than the mobile units, because it transmitted continuously. The Board concluded “that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated by Natarajan to apply the same power-conserving techniques to base units as it is disclosed with respect to mobile units, as well as that it would have been within the skill of the ordinarily skilled artisan to do so.” The Board found “no persuasive evidence of record that it would have been ‘uniquely challenging or difficult for one of ordinary skill in the art’ to do so.” Id. (quoting Leapfrog Enters., Inc. v. Fisher-Price, Inc.). The Board noted that, “as the [Supreme] Court explained in KSR, the skilled artisan is ‘a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton.’” (quoting KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc.). It ultimately found claims 1-2 and 9-10 obvious over Natarajan in view of of Neve, and DSS appealed. DSS’s Federal Circuit Appeal The Federal Circuit majority summarized the issue on appeal:

The sole issue on appeal is the Board’s finding that it would have been obvious to modify the base station transmitter in Natarajan to be “energized in low duty cycle RF bursts,” as required by the claims of the ’290 patent.

The majority launched into an analysis of the role of “common sense and common knowledge” in the obviousness inquiry. Three caveats were noted in applying “common sense”:

- First, common sense is typically invoked to provide a known motivation to combine, not to supply a missing claim limitation. (citing Arendi S.A.R.L. v. Apple Inc., 832 F.3d 1355, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- Second, we have invoked common sense to fill in a missing limitation only when “the limitation in question was unusually simple and the technology particularly straightforward.” Id. at 1362 (citing Perfect Web Techs., Inc. v. InfoUSA, Inc., 587 F.3d 1324, 1328 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

- Third, the cases “repeatedly warn that references to ‘common sense’—whether to supply a motivation to combine or a missing limitation—cannot be used as a wholesale substitute for reasoned analysis and evidentiary support, especially when dealing with a limitation missing from the prior art references specified.” Id.

The majority analogized the Board’s reference to “ordinary creativity” to the “common sense” considered in Arendi, and that calls for a “searching” inquiry. The majority observed that the limitation at issue is not “unusually simple” and the technology is not “particularly straightforward.” It relates to a complex communications protocol that enables the claimed low duty cycle mode of operation. The majority felt that the ’290 patent contemplated a server that was itself a mobile device and was stated itself to have an “extremely low power consumption” and that the pulsed mode of operation was critical to achieving this goal. Therefore, the majority found that the Board did not meet the standard set forth in Arendi. The majority isolated the Board’s analysis on this point:

The full extent of the Board’s analysis is contained in a single paragraph. . . . After acknowledging that Natarajan does not disclose a base unit transmitter that uses the same power conservation technique, the Board concluded that a person of ordinary skill would have been motivated to modify Natarajan to incorporate such a technique into a base unit transmitter and that such a modification would have been within the skill of the ordinarily skilled artisan. . . . In reaching these conclusions, the Board made no further citation to the record. . . . It referred instead to the “ordinary creativity” of the skilled artisan. Id. (quoting KSR, 550 U.S. at 420–21). This is not enough to satisfy the Arendi standard.

The majority was also critical of the Board’s reliance on Apple’s expert, Dr. Hu:

To the extent the Board’s obviousness findings were based on Dr. Hu’s testimony—which is questionable, because the Board never cited her testimony directly—her “conclusory statements and unspecific expert testimony” are insufficient to support the Board’s findings.

The majority concluded that the record was simply insufficient to warrant a remand for further findings and reversed the decision:

We also find “that this is not a case where a more reasoned explanation than that provided by the Board can be gleaned from the record.” Id. Dr. Hu’s testimony suffers from the serious deficiencies that we have discussed above, and Apple suggests no other evidence that might remedy those defects. Apple failed to meet its burden of establishing that the challenged claims of the ’290 patent were obvious. We therefore reverse the Board’s finding of unpatentability.

The Dissent By Judge Newman Judge Newman disagreed with the majority, stating that the proper decision was to remand for further explanation or “to decide the question of law” (presumably, obviousness). She asserted that the majority decision did neither. Judge Newman opined that the Board adequately explained its decision of unpatentability, and went into great detail to document the findings of the Board. She found the testimony of Dr. Hu, which the majority characterized as “conclusory” and “unspecific” as instead “directly on the point for which it was cited.” She also faulted the majority for not discussing or reviewing the evidence cited by the PTAB in its decision. Finally, Judge Newman explained that reversal is not a proper remedy for an inadequate explanation in the Board’s final written decision. Conclusion This case is valuable to show the depth of review that arises from IPR proceedings at the Board and Federal Circuit. It also provides valuable insight as to how the Federal Circuit interprets the use of “common sense” obviousness assertions in IPRs, post-KSR. It also raises discussion about the ramifications of an undeveloped record on appeal.

Back to All Resources